Demystifying our inflated calcium intake recommendations

Vegan Society of Canada News

Published January 23rd 2020

Updated January 24th 2024

Let’s continue to explore the broad impact of animal agriculture influence by looking at the inflated Canadian calcium recommendation. There is a lot of scientific evidence to go through and there is still more we do not know. The animal agriculture lobby as we have seen receive billions in subsidies that they use for numerous purposes, such as funding research. We always favor the scientific consensus and this has a better chance of being found in multinational organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) or a comprehensive multiple study review.

Let’s start by discussing what we do know. A lot of what we are outlining is the result of decades of research and discussions since the initial recommendation of the WHO in 1962 up to their report that was released in 2003 called “Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases”, and the report released in 2004 called “Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition, Second edition.”

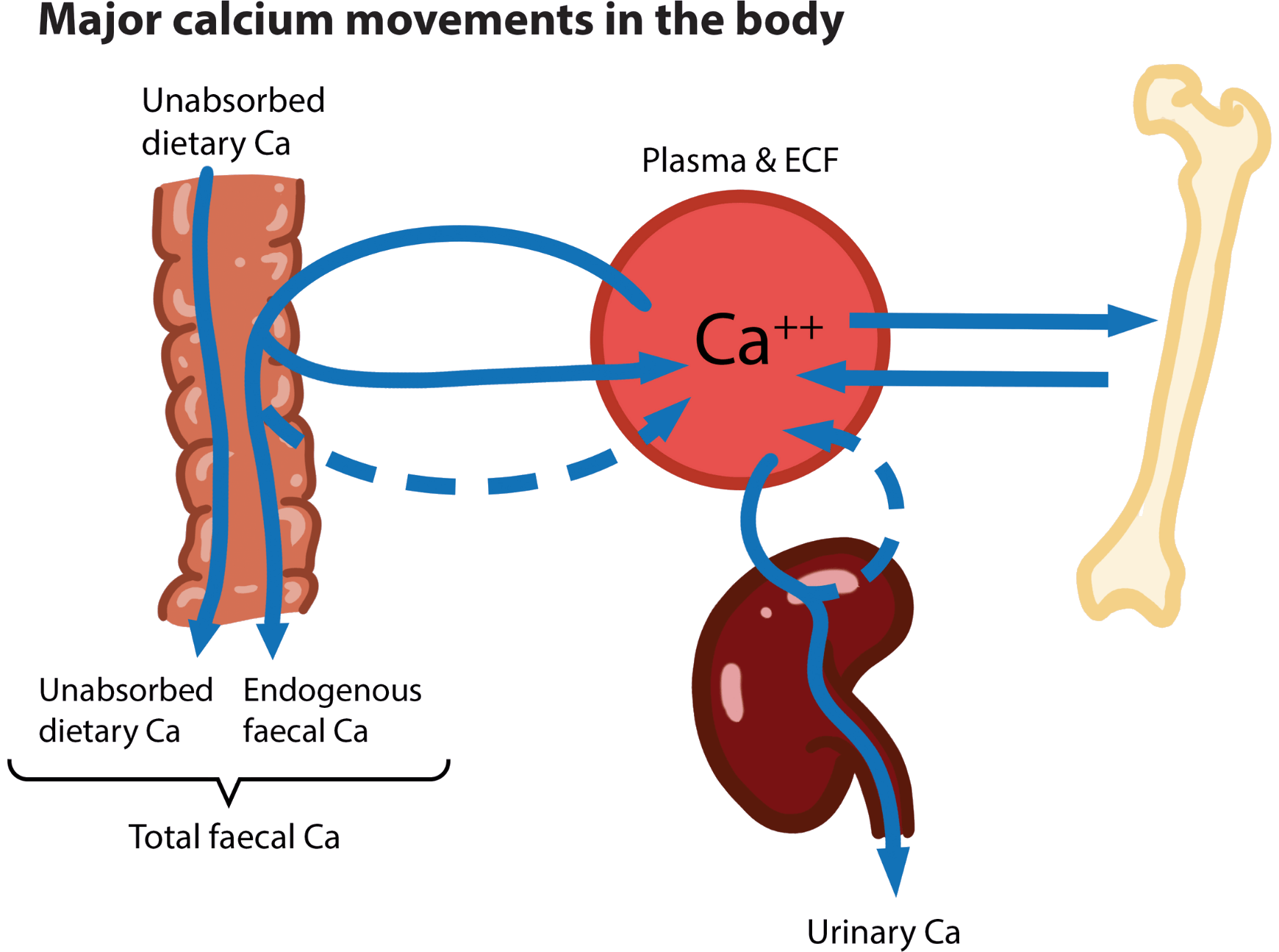

We know that 99% of calcium is in bones and while calcium is vital to many metabolic processes, globally our intake level of calcium is sufficient to address those and the main risk to skeletal integrity like osteoporosis. Below is an overview of calcium movement in the body:

We also know that like most other nutrients, bioavailability of calcium sources vary and absorption rate is influenced by various factors. Similar to many other nutrients, the more we ingest the less we absorb. On average the absorption rate of calcium in dairy is around 30%, kale and bok choy 50%, and broccoli 60%.

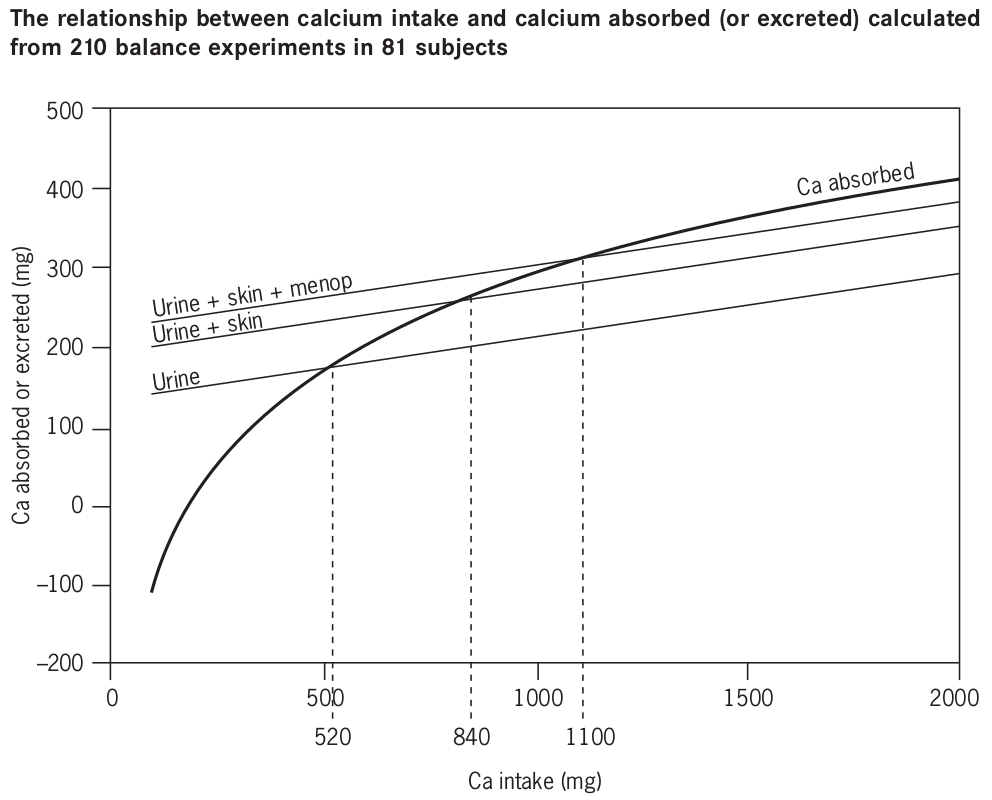

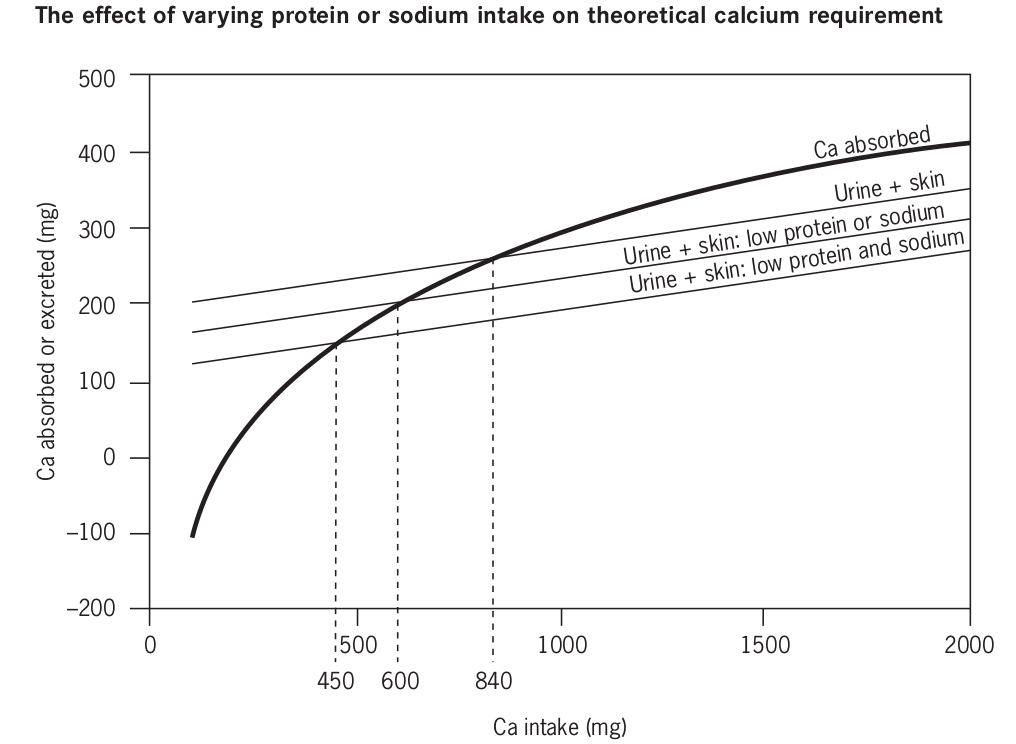

Ideally, if we had perfect knowledge and technology, we would have dietary recommendations perfectly tailored to each individual, taking into account various factors like genetics and gastrointestinal microbiota. Unfortunately this is currently impossible, so in the case of calcium the best we can do at this time is a balance study. A balance study means looking at a cross section of people for a period of time to determine an intake level at which the input of calcium is greater or equal to the outputs. The graph below shows the results when this was done with people in countries with a typical western diet:

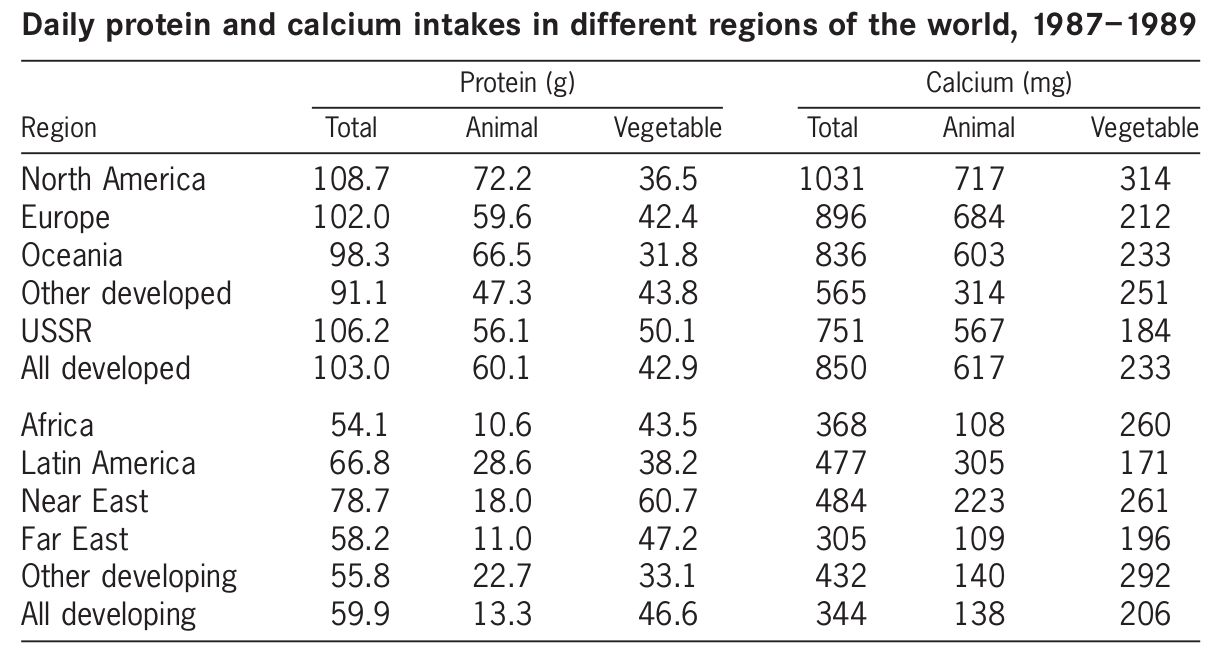

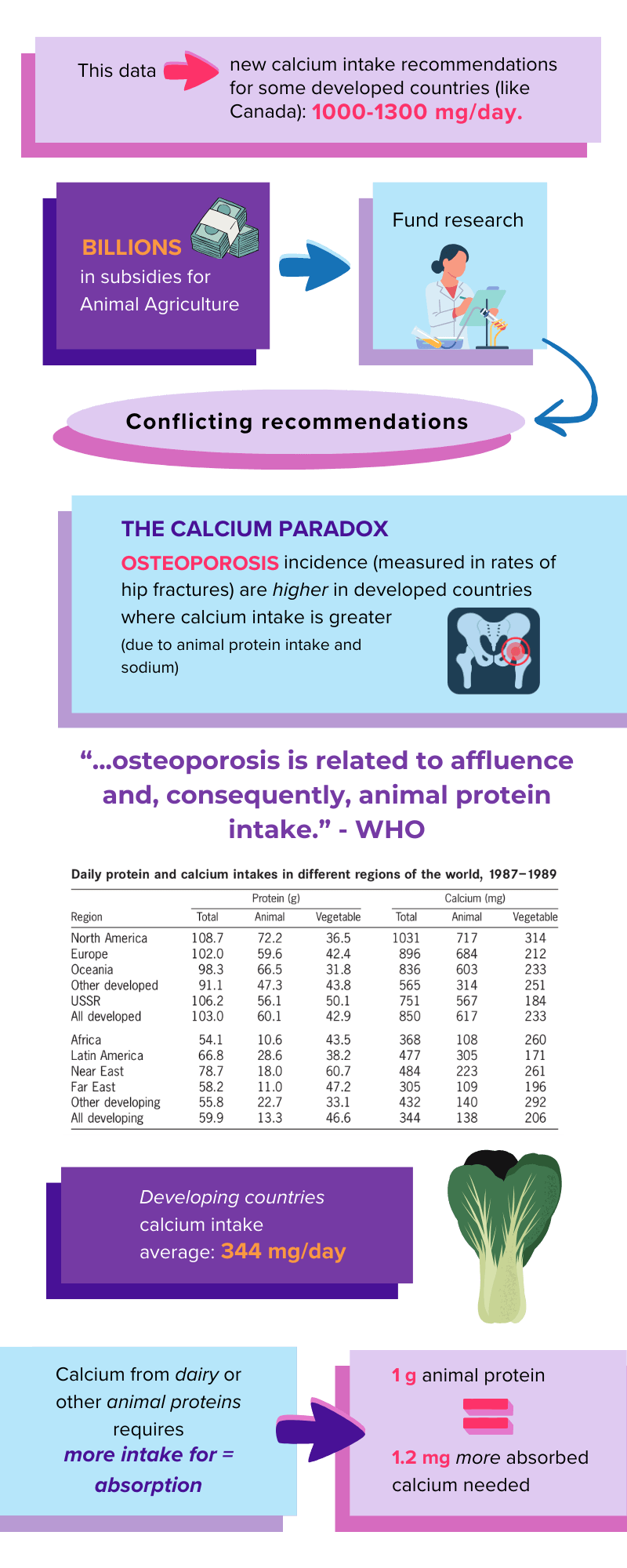

With this data, some developed countries with a typical western diet and strong agricultural lobby like Canada, USA, Australia and the EU got new recommendations hovering around 1000-1300 mg/day. The problem is there much we do not completely understand and that conflicts with this picture. Whenever there is such discrepancies in recommendations, it is often because the science is unclear, special interest groups are influencing the process, or a combination of both. We have known for decades about the calcium paradox: Osteoporosis incidence as measured by hip fracture rates are higher in developed countries where calcium intake is higher.

This is a big hole in our understanding. We tailor our calcium requirements to maintain skeletal integrity as measured by hip fractures, but in developing countries where calcium intake averages 344 mg/day instead of 1000-1300 mg/day hip fractures are lower.

We now have a few pieces of the puzzle to help explain this calcium paradox. First, we have known about the impact of animal protein for decades, yet we rarely hear about the fact that getting calcium through animal protein, like dairy products, means we need to take even more calcium. A review by the WHO determined that for each gram of animal protein we ingest, we need an additional 1.2 mg of absorbed calcium.

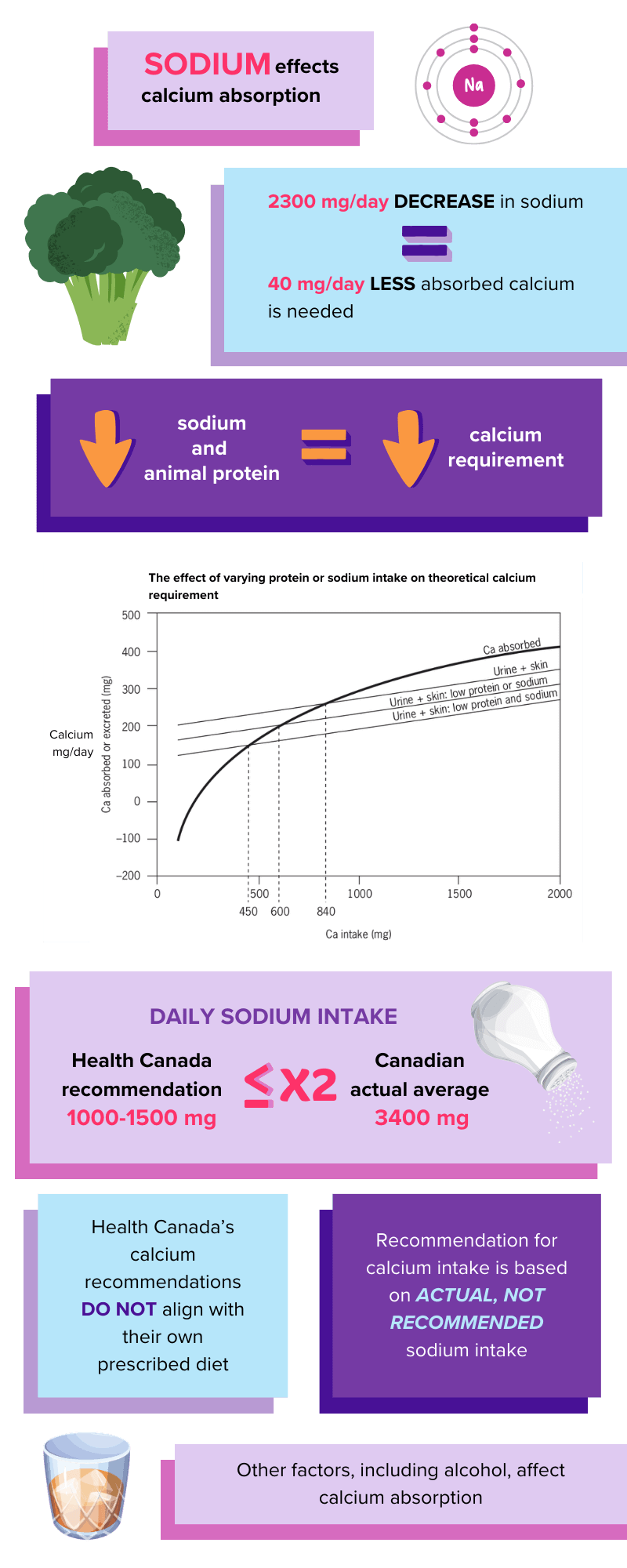

The other part of the puzzle is sodium. It has been known for decades that on average a reduction of 2300 mg/day of sodium in the diet reduces absorbed calcium requirements by 40 mg/day, or 133 mg of calcium intake based on a 30% absorption rate. The typical Canadian diet of packaged and processed food is filled with excess sodium; the average Canadian consumes 3400 mg of sodium per day or more than double the recommendation. The Canadian recommendation for sodium of 1000-1500 mg per day is not reflected in their calcium recommendation which takes into account the 3400 mg per day intake of the average Canadian. It is illogical to not advise that for anyone following Health’s Canada sodium recommendation their calcium requirements significantly drop.

Therefore lowering sodium intake from the typical Western diet of 3450 mg to 1150 mg per day and animal protein intake from 60 to 20 g per day, the WHO developed this graph:

With a Western-style diet, absorbed calcium matches urinary and skin calcium at an intake of 840 mg. Reducing animal protein intakes by 40 g reduces the intercept value and thus the requirement to 600 mg. Reducing both sodium and protein reduces the intercept value to 450 mg.

Now the calcium paradox starts to make sense. The same people that sell us dairy and cheese loaded with sodium are the same people that tell us that we need more dairy calcium.

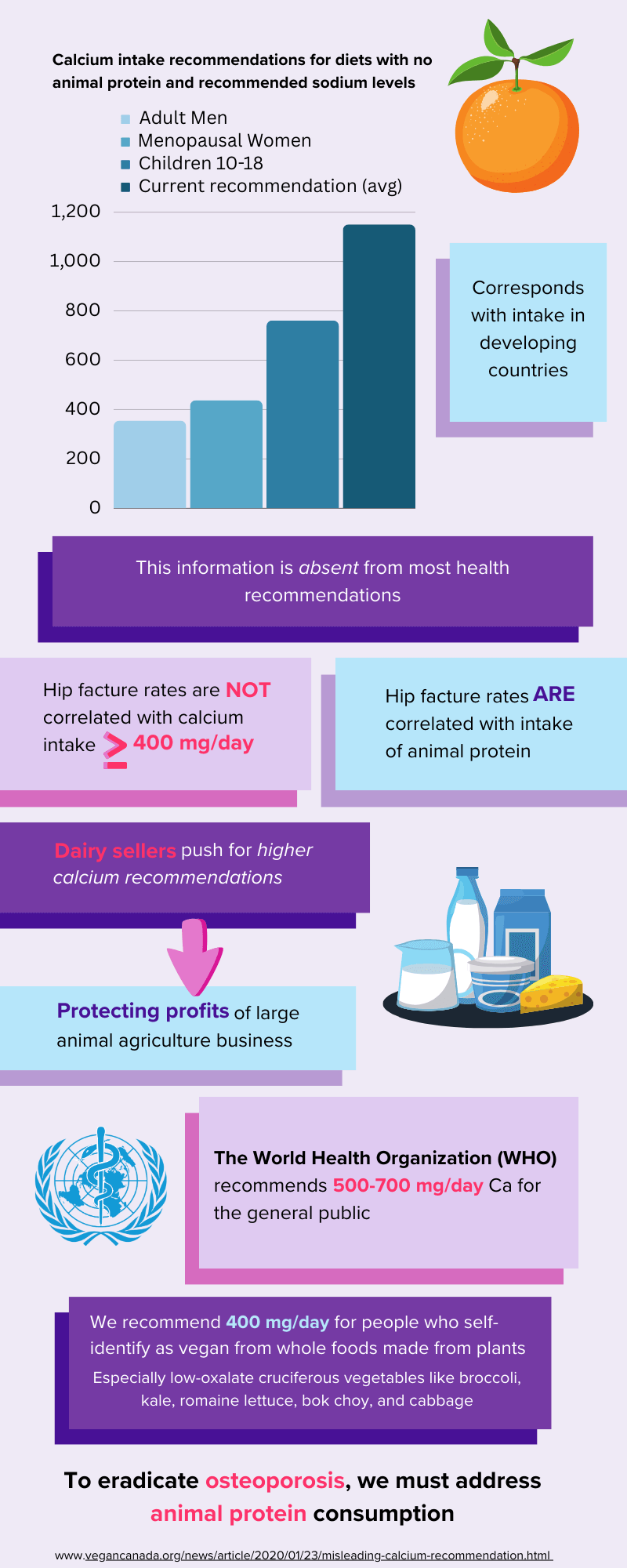

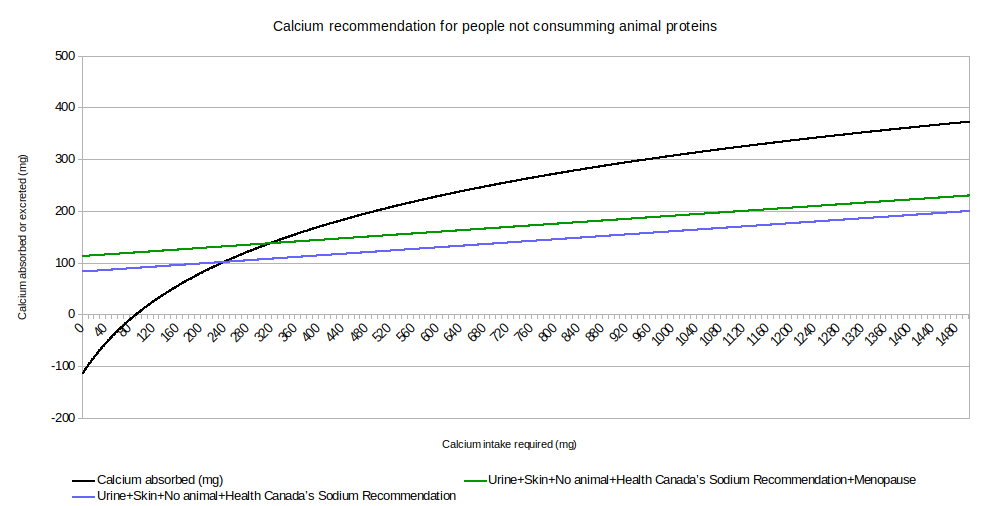

When we reduce animal protein intake to 0, for example to reflect those following a vegan lifestyle, we get the following:

Recommendations are 438 mg/day for menopausal women, 355 mg/day for adult men, and 761 mg/day for 10-18 years old. Once again, this is in line with observed intake of developing countries where animal agriculture is much less prominent and animal protein intake is much lower. It also, at least in part, explains the calcium paradox as to why people with lower calcium intake from developing countries, and to some extent those following eating food suitable for vegans, are not experiencing more hip fractures and by extension osteoporosis.

Furthermore, the calcium absorption curve is based on dairy, which has a lower bioavailability than various cruciferous vegetables but higher than some nuts, seeds, and beans. Therefore, depending on the specific diet, this would also have some influence, but since we have not found any randomized studies looking specifically at absorption rates of plant-sourced calcium under various intake within a vegan population, we believe it’s wise to stay with the absorption rate curve of dairy at 30%, which falls between some nuts, seeds, beans and cruciferous vegetables.

The WHO is clear:

There is no case for global, population-based approaches. A case can be made for targeted approaches with respect to calcium and vitamin D in high-risk subgroups of populations, i.e. those with a high fracture incidence.

Many other publications point to the same conclusion—that hip fracture prevalence (and by implication osteoporosis) is related to affluence and, consequently, to animal protein intake, as Hegsted pointed out, but also, paradoxically, to calcium intake because of the strong correlation between calcium and protein intakes within and between societies

The report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition made it clear that the recommendations for calcium intakes were based on long-term (90 days) calcium balance data for adults derived from Australia, Canada, the European Union, the United Kingdom and the United States, and were not necessarily applicable to all countries worldwide. The report also acknowledged that strong evidence was emerging that the requirements for calcium might vary from culture to culture for dietary, genetic, lifestyle and geographical reasons. Therefore, two sets of allowances were recommended: one for countries with low consumption of animal protein, and another based on data from North America and Western Europes.

We did not find any of this information on health organization sites, nor on Health Canada's page.

While it is completely understandable that information is not conveyed by the animal agriculture lobby—and to some extent from those who take money from the animal agriculture lobby like Dietitians of Canada, Osteoporosis Canada, and the Heart&Stroke foundation—it is a little more puzzling coming from Health Canada since their own food guide promotes a shift to a plant-based diet, and their own sodium recommendations are much lower than those used in the calculation of calcium requirements. Therefore, it would seem logical to update their calcium recommendations, or at the very least inform the public, with a level of animal protein and sodium that is in line with their food guide recommendations. We do not know the reasons behind the inflated Canadian calcium recommendation, and unfortunately, unlike the animal agriculture industry, we do not receive billions of dollars in subsidies to properly investigate this further.

There are many health crises currently, like obesity and the antibiotics crisis partly caused by animal agriculture, but certainly calcium intake is not one of them. When the WHO reports contains statement like:

Calcium absorption tends to decrease with age in both sexes but whereas there is strong evidence that calcium requirement rises during menopause, corresponding evidence about ageing men is less convincing. Nonetheless, as a precaution an extra allowance of 300 mg/day (7.5 mmol/day) for men over 65 years to raise their requirement to that of postmenopausal women was proposed.

This recommended intake (which is close to that derived differently by Matkovic and Heaney) is not achieved by many adolescents even in developed countries, but the effects of this shortfall on their growth and bone status are unknown.

One should seriously question the nature and motivation behind some of the revised guidelines based solely on countries with strong animal agriculture lobby and in many cases not based on any data but just as a “precaution”. Unfortunately, the WHO does not state a precaution, since they themselves acknowledged that there is no correlation with hip fracture where intake is higher or equal than 400 mg/day.

In countries with high osteoporotic fracture incidence, a low calcium intake (i.e. below 400--500 mg per day) among older men and women is associated with increased fracture risk.

Furthermore, they acknowledge that hip fracture and osteoporosis are related to increased animal protein intake. Moreover, bones act like a battery and 90-day studies, like those used to justify the increased recommendation in some countries, are not long enough to get an accurate picture of calcium balance in the long term. The only answer that seems fitting is that it is a precaution against the loss of profit by large animal agriculture corporations.

Ultimately the reason behind this is not important as the information is publicly available for everyone to read. While Health Canada is not discussing, let alone adjusting their recommendation to match their own Food Guide and WHO guidelines for people with low animal protein intake, we will. We are not the only ones recommending lower calcium intake not only for people with no animal protein intake but everyone else. Dr. Walter Willett, chair of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health recommends everyone lowers their intake. This also connects with the WHO finding that any calcium intake above 400 mg does not affect hip fracture rate and there is no scientific reason to justify higher intake.

We must remember that the original problem we were trying to address, with those revised guidelines that were in place since the 1960s, is the increase in hip fracture prevalence and by extension osteoporosis. However, the science tells us this is another problem that is linked to animal agriculture via a diet with a high amount of animal protein. It is illogical to try to remedy this problem by encouraging people to get calcium through more animal protein like dairy.

Vegan Society of Canada aligns with the WHO and the chair of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard and we advise adults following a vegan lifestyle and Health Canada’s sodium intake recommendation to aim for at least 400 mg of calcium from plants through whole foods, preferably low-oxalate cruciferous vegetables, which includes all greens except spinach, chard, and beet greens. If that is an issue on a daily basis, we recommend you supplement with a low dose calcium supplement. The “at least” is not because more is better, it is simply because it should not be possible to hit any upper limits with plant source of calcium from unfortified foods. Nevertheless, we will echo the WHO upper limit of 3000 mg for completeness.

There is a lack of scientific evidence evaluating the impact of different types of calcium supplements suitable for vegans. However, those sources not suitable for vegans—like calcium carbonate from animal bones and/or shell—have been shown in some cases to have various heavy metal contamination, as would be expected since our oceans are becoming a toxic sludge.

Another option is to make your own supplement by adding ½ cup of collard greens to your favourite smoothie for an extra 133 mg of calcium. If you need to sweeten it up, add a few dried figs at 13.4 mg of calcium per fig, molasses at 41 mg of calcium per tablespoon, or blackstrap molasses at 100 mg of calcium per tablespoon.

Since our last update there has been some new developments with regards to calcium supplements and cardiovascular that seems to further strengthen the case for being cautions. A meta-analysis of 13 studies and 14243 participants showed that calcium supplements increased the risk of CVD by about 15% in healthy postmenopausal women. Therefore, we continue to also recommend staying below 500 mg/day if using supplemental calcium, even if that means possibly getting less than the amount we are aiming for, until we know more about the connection between calcium supplements and heart attacks.

Discussing dietary recommendations in a vacuum is both unethical and irresponsible. As such we support Health Canada’s recommendation to Canadians:

Food choices can have an impact on the environment. While health is the primary focus of Canada’s Dietary Guidelines, there are potential environmental benefits to improving current patterns of eating as outlined in this report. For example, there is evidence supporting a lesser environmental impact of patterns of eating higher in plant-based foods and lower in animal-based foods. The potential benefits include helping to conserve soil, water and air.

Therefore for the general public, we would encourage instead of trying to increase their calcium intake to simply adopt a vegan lifestyle and Health’s Canada sodium recommendation. The health benefits will be numerous, the benefits to the planet and countless living beings are also many.

Otherwise we echo the recommendation of Dr. Walter Willett, chair of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health to aim for 500–700 mg/day for the general public and to take into account various lifestyle factors like sodium and alcohol intake which affects calcium absorption.

It is clear that when the WHO says:

Many other publications point to the same conclusion—that hip fracture prevalence (and by implication osteoporosis) is related to affluence and, consequently, to animal protein intake, as Hegsted pointed out, but also, paradoxically, to calcium intake because of the strong correlation between calcium and protein intakes within and between societies.

Anyone who is truly interested in eradicating hip fracture, and by extension osteoporosis, must also be interested in eradicating animal protein and switching from the typical western lifestyle. Any other actions are equivalent to bailing a sinking boat with a spoon. It seems clear when a “health” organization allows sponsored content like this masquerading as a public health message that they are not interested in eradicating osteoporosis at all.

We may as well be the osteoporosis prevention organization in Canada since getting Canadians to change their affluent lifestyles filled with animal protein is much more scientifically likely to reduce hip fractures, and by implication osteoporosis, than anything else.

In future articles we will expand our other nutritional recommendations based on science, as dictated by our mission and one of our charitable purposes to protect and promote the health of Canadians.

Here is a table of plant calcium with approximate absorption rates if available. Please note that we have not added fortified foods since this is the same as taking a supplement, therefore fortified orange juice is the same as a non-fortified orange juice with calcium powder mixed into it.

| Food Source | Calcium (mg) | Absorption Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Collards (1 cup, boiled) | 268 | |

| Soybeans (1 cup, boiled) | 261 | |

| Spinach (1 cup, boiled) | 245 | 5.1 |

| Mustard greens (1 cup, boiled) | 165 | 57.8 |

| White beans (1 cup, boiled) | 161 | 17 |

| Cabbage, Chinese (1 cup, boiled) | 158.1 | 53.8 |

| Bok Choy (1 cup, boiled) | 158 | 53.8 |

| Figs, dried (10 medium) | 136 | |

| Navy beans (1 cup, boiled) | 128 | |

| Great northern beans (1 cup, boiled) | 120 | |

| Chick peas (1 cup, canned) | 109 | |

| Black turtle beans (1 cup, boiled) | 102 | |

| Swiss chard (1 cup, boiled) | 102 | |

| Blackstrap molasses (1 tbsp) | 100 | |

| Kale (1 cup boiled) | 94 | 58.8 |

| Butternut squash (1 cup, boiled) | 84 | |

| Pinto beans (1 cup, boiled) | 79 | 17 |

| Sweet potato (1 cup, boiled) | 76 | |

| Cabbage, green (1 cup, boiled) | 72 | 64.9 |

| Broccoli (1 cup, boiled) | 62 | 52.6 |

| Barley (1 cup) | 61 | |

| Brussels sprouts (8 sprouts) | 60 | 63.8 |

| Navel orange (1 medium) | 60 | |

| Green beans (1 cup, boiled) | 55 | |

| Raisins (2/3 cup) | 54 | |

| Rutabaga (1 cup, boiled mashed) | 43.2 | 61.4 |

| Molasses (1 tbsp) | 41 | |

| Radish (1 cup, raw sliced) | 29 | 74.4 |

| Cauliflower (1 cup, boiled) | 19.8 | 68.6 |